Why do sand dunes matter?

The coastal dunes of England and Wales are internationally important habitats for wildlife.

72 important sand dune species in England and Wales live here amongst two priority habitats.

Dunes are highly diverse environments, home to a variety of orchids and many insects and ground nesting birds. The damper dune slacks are the perfect habitat for amphibians such as the rare and protected natterjack toad – Cumbria is home to over a quarter of the UK’s natterjack toad population!

Dunes are also full of history, they provide a place for recreation and tourism, ecosystem services as well as beautiful views and are a place to be enjoyed as well as protected.

What are sand dunes?

A sand dune is a hill or ridge beyond the reach of the tides. Dunes begin life as a singular grain of sand or shell fragment, blown inland by the offshore winds which accumulate on vegetation above the strandline. Overtime, our distinct mountains of sand have formed, standing at the forefront of our coastal weather systems and naturally shifting.

Healthy, dynamic dune systems support a variety of habitats and species.

North Walney dune formation © Steve Benn

Embryo/frontal dunes

Sand is trapped by obstacles moved by wind and waves. Above the high tide line embryo dunes develop and pioneer plants establish including sand couch and lyme grass.

Marram grass grows as fast as the sand builds and starts to dominate, accumulating sand to form higher mobile dunes. Specialised plants may include sea holly. Sand lizards and northern dune tiger beetles rely on bare sand here too.

Eskmeals Dunes © John Morrison

Fixed dunes/ dune grassland

As marram dominates, bare sand cover is reduced. Mosses and grasses start to grow. Soil begins to form and many plants and wildflowers coexist, including the pretty dune gentian and bee orchid.

Species diversity here is rich; ground-nesting birds such as skylarks thrive here, while rabbits burrow and solitary bees roam.

Dune Slack and fixed dunes © Jim Turner

Dune slack

These are the hidden gems of any dune system. Low-lying, wind-blown wet depressions within the dunes are vital breeding pools for natterjack toads and a habitat for great crested newts and a variety of invertebrates.

The surroundings can support a range of orchids such as coral root and marsh helleborine and other flora including round-leaved wintergreen. Sedges and creeping willow thrive.

North Walney dune heath © Steve Benn

Dune heath

This is priority habitat, as it is becoming increasingly scarce in the UK. Soil is dry and acidic. Heather is abundant and provides for ground nesting birds and insects. Dune heath can be calciferous too.

Eskmeal Dunes 2013. Steve Pipe

Scrub and Woodland

In the late successional stages of dune systems, you can find dominance of tall, woody perennials and understorey species. Very little, if any, bare sand is present here. The habitat provides important shelter for birds and mammals.

Eskmeal Dunes 2013. Steve Pipe

Natural disturbances

Storms create blow outs (new areas of exposed sand at the front or within a dune system), rabbits burrow into the dunes and visitors can trample, creating areas of bare sand. This kick-starts the earlier successional stages, forming patches of different habitat throughout the dune system, supporting a range of biodiversity.

Why do sand dunes need restoring?

Sand dunes are the most at risk habitat in Europe for biodiversity loss. There are only 20,000 hectares of dunes left in England and Wales.

Dunes have become overgrown with vegetation and have stabilised. This is due to a variety of factors that have slowly impoverished the dunes over many decades. Factors include: conventional dune-stabilising management, change in land use and grazing regimes, nitrogen deposition and climate change, an increase in invasive species and widespread vegetation growth, and even significant local loss of grazing rabbit populations from disease.

These issues have impeded the natural dynamic nature of sand dunes; healthy dunes need areas of shifting sand in which bare sand-loving plants and animals can survive, but the older, less-mobile ecological succession stages of sand dunes have taken over. Increased vegetation has reduced the variety of dune habitats present which specialised species rely on to thrive, threatening the special biodiversity that lives there.

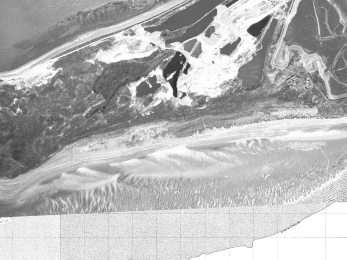

Changes in Cumbrian sand dunes over the decades:

These historical aerial images are of South Walney Nature Reserve. The white on the 1960’s photo show areas of bare sand as part of a healthy dune system. See how the dunes have changed over time.

In this instance, large gull colonies nesting on site overtime caused a layer of nutrient rich soil to build on top of the sands, contributing to the vegetation growth seen in the more recent image. Subsequently there has been natural decline of these populations.

Dynamic Dunescapes

Dynamic Dunescapes works to restore sand dunes across England and Wales for the benefit of wildlife, people and communities, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the EU LIFE Programme. Project partners include Cumbria Wildlife Trust, Cornwall Wildlife Trust, and Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust, as well as Natural England, Plantlife, National Trust, and Natural Resources Wales.

The coastal sand dunes of England and Wales are internationally important habitats for wildlife, and listed as one of the most threatened environments in Europe for biodiversity loss. Dunes are a sanctuary for rare species like orchids, sand lizards, and natterjack toads. However, dunes are suffering from widespread over-stabilisation,

invasive species, habitat loss, and vegetation growth due to changes in land use and grazing regimes, loss of rabbit populations, climate change and nitrogen deposition.

Healthy sand dunes need to be free to move and be dynamic. Many species need areas of open sand to thrive, so this project's intent was to bring life back to the dunes by restoring and creating habitat types that specialised dune wildlife need.

What have we done to help the dunes?

- Removal of invasive species including Japanese rose and sea buckthorn

- Introduction of grazing regimes including cattle with no fence collars in Cumbria, and ponies in Cornwall.

- Pond creation & restoration - Natterjack toads rely on seasonal flooding to keep the dune slacks wet enough for them to breed in.

- Turf stripping (removing the top layer of soil to expose the bare sand below)

- Notch creation (creating V shaped gaps in foredunes to allow sand from the beach to be moved through the dune system by the wind)